3 Types of Pain in the Butt and What You Can Do About It

/Having a literal pain in the butt is not a fun experience; it can make walking, sitting and sleeping difficult and uncomfortable. It is certainly something that one would want gone as soon as possible, yet sometimes we unknowingly exacerbate the issue by trying to stretch the injured area. There is a special name for these types of practices – anga bangha. It basically means that you want to do something good but end up hurting yourself. Today we will explore three types of the pain in the butt and how you can avoid making your practice anga bangha.

Pain in the butt #1: Lower butt pain.

Many years ago I was preparing for a fitness competition and my routine included a split. One day, being young and silly, I plopped into the split right off the bat and heard “Crrkkhh” at the bottom of my right buttock. “Hmm, I thought, that didn’t sound too good”. I did manage to get out of the split, but ended up limping for couple of weeks and then dealing with the pain in the butt for months afterwards.

Location: This is the pain that you experience right in the crease of the buttock at the back of the thigh. It might give you trouble when you walk, but becomes especially pronounced when you bend forward with legs straight.

Offender: Hamstring tendon(s)

Reason: This type of pain is usually a sign of an injury to the tendon(s) that attach your hamstrings to the pelvis. It is usually a result of pulling on the hamstrings too enthusiastically, especially if they haven’t been warmed up properly. When yoga practitioners insist on keeping the legs straight in forward bends and then force themselves into a pose, they may end up injuring the tendon. Yoga teachers who demonstrate a lot in their classes are also at risk, since they are more likely to go into a difficult posture without proper preparation.

Common remedy: Here is the paradox – when the tendon becomes injured, the hamstring muscles naturally contract, trying to prevent further damage to the tendon. And we think – my hamstrings feel tight and painful, if I only stretch them the pain will go away. So instead of allowing the tendon to heal, we keep reinjuring it by actively stretching the hamstrings. This cycle can go on for a very long time.

Better solution: Give your tendon(s) a chance to heal. This means contracting the hamstrings to increase circulation to the area, bending the knees generously in the forward bends and only very mild stretching, if any. Once the acute phase has passed, you can begin to add gradual stretching.

Nurse your hamstrings back to health

Try this short 3-stage yoga practice to gradually heal your injured hamstrings. You can also use this practice to release chronic tension in your hamstrings.

Pain in the butt #2: Outer/upper butt pain.

I have a client who came to me complaining about the pain in the hip that interfered with her walking and sleeping. She has been to a PT who suggested core strengthening, an orthopedic surgeon who diagnosed her with piriformis syndrome, and LMT who treated her for a tight IT band. After careful exploration we have determined that the location and symptoms of her pain were pointing toward the weakened abductor muscles, which caused a displacement of the pelvis and a host of muscle compensation patterns. We began to work on strengthening her abductors and shortly after her pain was gone.

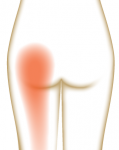

Location: This type of pain usually shows up in the upper or outer buttock area and can resonate down on the side of the leg. It usually gets worse during walking and while lying on the affected side at night.

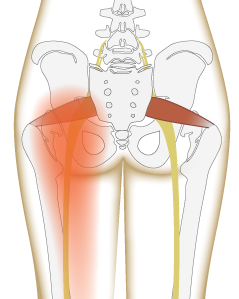

Offender: Weak abductor(s), tight IT band can be a contributing factor

Reason: This pain is often due to some sort of an asymmetrical movement pattern that goes on for an extended period of time (read more about adductor/abductor imbalance).

Common remedy: This pain is often perceived as an IT band issue and remedied by stretching the IT band or using the roller to apply pressure to it. This can be very useful, but it does not address the root of the problem – weak abductors. Until those are strengthened, the issue will continue to pop up.

Better solution. You need to strengthen the abductors by using them in the stabilizing role (standing on one leg) and moving role (moving the leg out to the side, preferably against gravity). Here is a sample practice for abductor strengthening.

Pain the butt #3: Central butt pain.

When the Body Worlds exhibit came to town, one of the reasons I went was to check out the structure of the hip, since I do not have ready access to cadavers. Yes, it was creepy at times, but also fascinating. For example, I was amazed at how big the sciatic nerve is – yes, it’s the longest nerve in your body, extending from the lower spine all the way down into the foot, but it’s also very thick – about the thickness of your pinky finger – between your spine and hip area.

Since the nerve is so big and long, it can get pinched at various locations causing all-too-familiar sciatic pain. Two common sites of impingement are the lower back (between the lumbar vertebrae) and underneath the tight piriformis muscle.

Piriformis is a small muscle that can cause a lot of trouble if it gets tight. It sits deep within the hip and its job is to rotate the hip externally and to abduct the leg when the hip is flexed. Tight piriformis by itself can cause the pain in the butt, but situation becomes worse if it presses on the sciatic nerve that passes underneath (and for some people right through) the piriformis muscle.

Location: The pain can show up in the middle of the buttock, in the lower back or anywhere along the pathway of the nerve. It can also manifest as numbness or weakness in the leg.

Offender: Herniated disks, bone spurs on the vertebrae or tight piriformis muscle

Reason: Sitting or driving a lot, degenerative changes in the spine with age

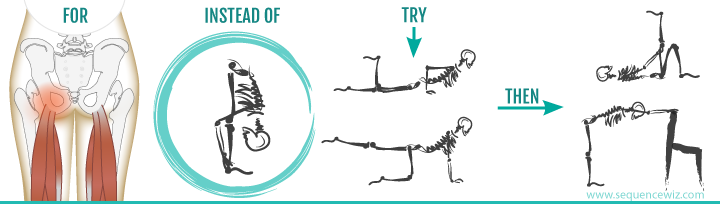

Common remedy: If the sciatic pain is due to a herniated disk, it is a much bigger issue and is beyond the scope of this post. Core strengthening under the guidance of a physical therapist would be the best solution. If the pain is due to the tight piriformis muscle, we can work on releasing the muscle tension. The most commonly recommended pose for the tight piriformis is Pigeon pose. Unfortunately, for many people with this type of pain this is too much, too soon. Pigeon pose places the piriformis in the maximum stretched position and pulls strongly on the sciatic nerve as well. This means that if the pain is acute, getting onto the Pigeon can make it feel worse.

Better solution: It makes much more sense to utilize our usual Contract-Relax-Stretch principle.

Step 1. We begin by contracting the SURROUNDING muscles (particularly gluteus maximus) to increase the blood flow into the general area.

Step 2. Then we can gently contract the piriformis muscle itself, asking it to relieve the chronic contraction (only if it doesn’t cause pain) in combination with gentle stretching. Poses like Virabhadrasana 2, Utthita Parsvakonasana and versions of clam shell will contract the piriformis, while simple standing twist with a chair and Ardha Matsyendrasana would be good options for stretching it (since they place your leg into flexed/adducted position without the external rotation element, which is milder for piriformis).

Step 3. When you are ready to add the external rotation element to your stretching, it’s better to choose Thread-the-needle pose instead of Pigeon, or Gomukasana on the back instead of the full form of the posture, which will apply less leverage against your piriformis. Only after practicing those you’ll be ready for Pigeon or Gomukasana (and some students won’t be ready for a long time if ever).

In addition, it makes sense to relieve chronic contraction in the adductors, since tight adductors can internally rotate the leg, placing additional stress on the piriformis muscle. Tight hamstrings can also irritate the sciatic nerve, so it is useful to relieve tension there. Keep in mind, that even the simplest hamstring stretches can be very painful to a student with sciatica, so it’s best to follow the same principle for hamstring work that we’ve outlined in Pain in the butt #1.

So there you have it. Keep in mind that sometimes there can be multiple things going on, so if your pain persists despite your best efforts, it’s probably time to seek professional help.

Here is a sample practice to relieve tension in the piriformis muscle, using all the principles we’ve outlined above.

Written by Olga Kabel. For the full article visit here.

![Self-regulation “control [of oneself] by oneself"](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55563e14e4b01769086817cb/1542845645966-PO2HGKF5JLUBM45UIWQ3/wee-lee-790761-unsplash.jpg)