These Pictures Will Help You See Which Muscle You’re Stretching

/Stretching is something not enough of us do, but its importance is critical. But it’s hard to see which muscle you’re stretching, because your skin is in the way of viewing your muscular structure underneath!

Stretching helps send blood flow to your muscles and helps your joints move through their full range of motion. It improves your posture, gets rid of tightness, and lowers your risk of pain and injury.

With these 36 pictures (created by Vicky Timon, a yoga expert and author of “Encyclopedia of Pilates Exercises”), you’ll be able to choose the best stretches for your goals. As you stretch, make sure you focus on your breath and move through these movements as naturally as possible.

It can take 5-30 seconds for your muscles to relax back into their natural positions, so take it slow, breathe through it, and help heal your body!

1. Camel Pose

Muscle Stretched: Rectus Abdominus and External Obliques.

Also known as the “heart opening” yoga pose, camel is great for helping clear the heart and throat centres. It should not be performed if you have a low back or neck injury. It is most appropriate for those who already have good flexibility. Come on your knees and place the knees hip-width apart, body upright. Place your hands on your lower back, pushing your hips forward. Slowly drop your head back and reach for your feet if your hips remain pushed forward, but don’t put your hands back on your feet if your hips fall back. Do not put too much pressure on your lumbar spine. Once in full position, keep pushing your chest up into the air.

2. Wide Forward Fold

Muscle Stretched: Adductors.

A great stretch for helping open the hips. Bend your knees and hold your spine straight. As your muscles begin to release, straighten your legs, round your back and reach for your feet. Pull on the bottom balls of your feet to release the calf muscles. If you are new to this pose, you likely will not be able to reach your feet. Simply keep your hands on your calves and stretch down.

3. Frog Pose

Muscle Stretched: Adductors.

One of the most deepest stretches for the groin, frog pose is one of my favourites. Perform it on a soft surface to avoid putting too much pressure on the knees. Rest your hands and knees, and then bring your knees wider until you can feel your groin muscles starting to stretch. Push your hips back and forward lightly to ease into the stretch.

4. Wide Side Lunge Pose

Muscle Stretched: Adductors.

Put both your feet forward in a wide stance and hold your legs as straight as possible. With your hands, walk to your right foot and bend your right knee and rotate your left toes up to the ceiling, sitting in your right hip. Make sure your right foot stays flat on the ground.

5. Butterfly Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Adductors

This one is great for stretching the inner thighs. Bring the soles of your feet together and sit tall through your sit bones. Put some pressure on your knees, using your hands, or if you are really advanced, get someone to stand on top of you with their feet on either leg. For a deeper groin stretch, hold your feet closer to your body. You can also bend your body forward over your feet for more effect.

6. Forearm Extensor Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Forearm Extensor.

Begin with your arm in front of you with your wrist flexed toward the inner portion of your forearm. You should feel a stretch int he muscles that line your outer forearm. This stretch can be developed by touching the tips of your fingers together in the shape of a tea cup.

7. Lateral Side Flexion of the Neck

Muscle Stretched: Sternocleidomastoid “SCM”.

Look forward and don’t let the chin drop down for this stretch. Slowly move your ear towards the shoulder, without letting your shoulder lift up. A more advanced variation would be to sit on a chair and hold onto the bottom of the seat with both hands. This will make the tension down your arm and neck consistent, letting you target the upper traps.

8. Neck Rotation Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Sternocleidomastoid “SCM”.

Start rotating your neck slowly, while keeping your chin a bit elevated. For a deeper stretch, put pressure with the opposite hand from the direction that you are rotating.

9. Neck Extension Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Sternocleidomastoid “SCM”.

Put your hands on your hips, while keeping your spine long. Start to tilt your head back, ensuring that you are not collapsing your cervical spine.

10. Lateral Side Flexion of the Neck with Hand Assistance

Muscle Stretched: Sternocleidomastoid “SCM” and Upper Trapezius.

Look forward and don’t let the chin drop down for this stretch. Slowly move your ear towards the shoulder, with gentle pressure from your hand (without letting your shoulder lift up).

11. Half Kneeling Quad / Hip Flexor Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Psoas and Quadriceps.

Start by half-kneeling. Then, bring forward the right hip. You should start feeling a stretch in the front of your hip while you do so. Take your back foot and squeeze your back flute in order to add to the stretch on your hip flexors.

12. Forearm Extensor Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Forearm Extensor.

Rotate your should towards the outside to get into the optimal forearm-stretching position. When you have come into this position, put pressure on your opposing hand to start the stretch.

13. Lateral Shoulder Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Side Deltoid.

Stand up tall with your right (or left) arm extended and holding your right elbow with your left hand (or vice versa). Slowly pull it across your chest until you feel a gentle stretch in your shoulder.

14. Standing Assisted Neck Flexion Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Trapezius Muscle.

I really love this stretch, as it gets the muscles in the back of the neck and shoulders, where we hold a lot of tension. Stand on the ground with your feet together. Slowly sit your hips back, making sure the spine is prolonged. Round your upper back, pushing your chin into your chest at the same time.

15. Lat Stretch with Spinal Traction

Muscle Stretched: Latissimus Dorsi.

Take a firm grip of a bar and slowly lift your feet off the ground. You will feel the stretch in your chest and lats. If you have taken your feet totally off the ground, you will feel traction in your lumbar spine. Do not perform this stretch if you have undergone any type of shoulder injury or have impingement of the shoulder.

16. Lat Stretch at the Wall

Muscle Stretched: Latissimus Dorsi.

Put both of your hands on the corner of a wall or post. Maintaining a long spine, gently push your hips out to the side. People with lower back problems should not perform this stretch.

17. Child’s Pose

Muscle Stretched: Latissimus Dorsi.

A very relaxing stretch, this one starts with you on the ground with your hands and knees on the floor. Slowly bring your hips back until your forehead is on the floor. If you want a better hip stretch, bring your knees wider. Your upper back should be in arch shape, and then you should externally rotate your shoulder to stretch your chest and lat muscles.

18. Standing Calf Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Soleus and Gastrocnemius.

This can be performed on the edge of a stair step or wall. Rotate your ankles a bit towards inside and outside to actively stretch your calf muscles.

19. Front Split

Muscle Stretched: Psoas and Hamstring.

If you are new to stretching and yoga, do not perform the front split. Begin in a position of kneeling lunge, and slowly lower your hips to the ground, while keeping them square to the ground. Use your hands for support on either side of you. If you feel any pain, get out of the pose immediately. You can also use the support of a chair while your hip flexors and hamstrings release.

20. Seated Forward Fold / Seated Toe Touch

Muscle Stretched: Hamstrings and Calfs.

Sit into your seat bones and bend your knees if you have to. Make sure your spine is as straight as possible as you grab your feet and pull forward and down. If you can’t reach your feet, reach the next thing closest, like your calves (or bend your knees).

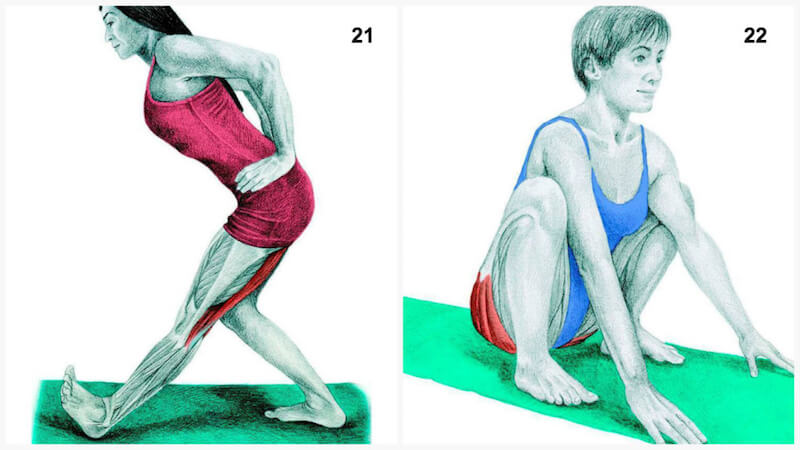

21. Single Leg Forward Bend

Muscle Stretched: Hamstrings.

Have your feet positioned one in front of the other. Keep your back straight, and bring your hands to your hips and start bending from the hips.

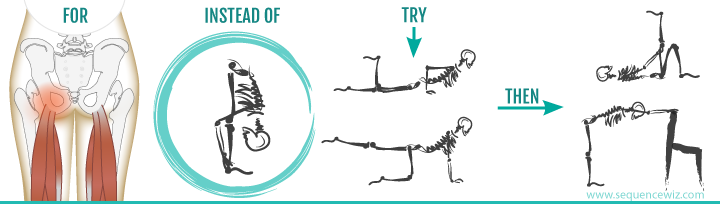

22. Deep Squat

Muscle Stretched: Glutes.

A deep squat is great for many body areas. If you have knee problems, or you can’t keep your heels on the ground, perform your squat before proceeding. Stand your feet shoulder-width apart and gradually lower into the deep squat. When you get into the position of a deep squat, bring your arms inside your legs and put some pressure to the inside of your knees, sitting into the hips and heels. This can also be performed lying on the back with the feet against a wall.

23. Seated Half King Pigeon Pose

Muscle Stretched: Glutes.

Start in a seated position and slowly pull your leg to your chest and rotate your hip towards the outside, while keeping your spine straight. The stretch should be felt in the glute.

24. Standing Calf Stretch at the Wall

Muscle Stretched: Soleus and Gastrocnemius.

Get in a lunge position and have the back of your foot turned out a little. Gradually bring the back of your heel to the floor to stretch your calf muscles.

25. Lateral Flexion at the Wall

Muscle Stretched: External Obliques.

Keep your spine long, and slowly push your hips to the outside. If you have issues with your lower back, do not perform this stretch!

26. Supine Twist

Muscle Stretched: Glutes and External Obliques.

This is a great stretch for the IT band in the leg, and is beneficial for those suffering from sciatica pain, who are trying to get rid of it. Start by lying flat on your back and then bring one leg across your body. Gradually rotate your gaze and upper body in the opposite direction. Breath into this one to help open up your rib cage and sacroiliac joint and hip area. If this is too hard for you, stack your knees on top of one another – doing this will make you feel the stretch more in the upper spine when the knees are higher, and more in the lumbar spine when the knees are lower.

27. Lateral Flexion with a Dowel

Muscle Stretched: External Obliques and Latissimus Dorsi.

Keep your spine long, and gradually push your hips out to the side while keeping your shoulders rotated outwardly while holding onto a dowel. If your lower back hurts, do not perform this stretch.

28. Triangle Pose

Muscle Stretched: External Obliques.

The master pose, triangle. Begin with a wide stand and your front foot straight ahead, and your back foot at a 90 degree angle. Put your hand on your front leg or on the floor, and sit back into your front hip, keeping your back straight. Rotate away from your front leg and maintain your gaze at the hand that is in the air. Eventually you can do this pose by bending your foot that is at the 90 degree angle so that you are in a lunge almost, with hips facing forward.

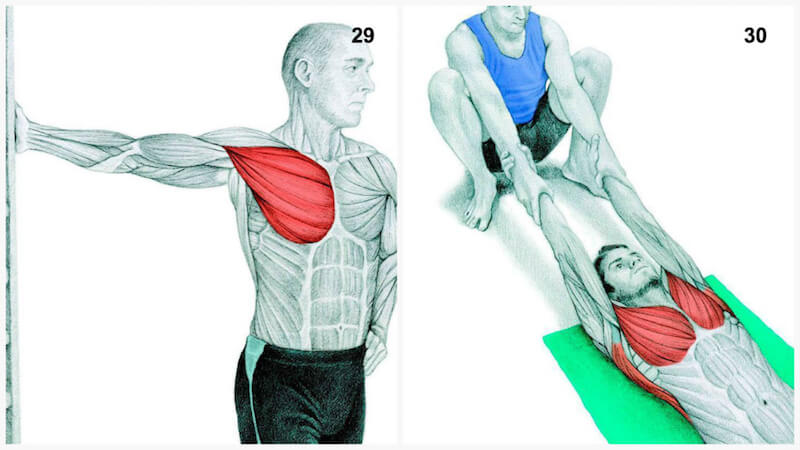

29. Chest Stretch at the Wall

Muscle Stretched: Pectorals.

Stand facing a wall. Place your right palm on the wall so that it is in line with your shoulder. Keep your right hand planted firmly and bend your left arm behind you to encourage opening of the left shoulder. Now, walk your feet to the left and stop when you feel a good stretch in your right shoulder and chest. Repeat on the other side.

30. Assisted Chest Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Chest and Latissimus Dorsi.

Lie down not he floor and hold your palms faced up. Your partner should be in a deep squat just a little behind where your head is rested, while holding your hands. This stretch will be felt in your chest and lats, and should also cause some traction in your spine. If your shoulder dislocates or has dislocated recently, do not perform this stretch.

31. Seated Half Pigeon Variation

Muscle Stretched: Anterior Tibialis.

Sit with your feet positioned in front of you, and put one hand behind you and rotate your hip outwardly and put one foot above your knee. If you want to add to the stretch on your hip, lean forward and start the movement by hinging at the hips.

32. Supine Shoulder External Rotation Stretch

Muscle Stretched: Subscapularis.

Lay flat on your back and place your arm straight out to the side with your elbow at a 90 degree angle. Gradually bring the back of your hand to the floor. If this is not possible, it means your rotator cuff and other muscles that control internal rotation are tight. Breathe into the stretch and press the back of your hand down as much as possible without pain.

33. Down Dog Variation at the Wall

Muscle Stretched: Pectorals and Latissimus Dorsi.

Stand in front of a wall of rack, enough so that when your body is in a parallel position, you will have enough room. Pivot at the hips, making sure your spine is straight at all times. Move your chest forward and make a slight arch in your upper back and stretch your lats and chest muscles. If your hamstrings are too tight, bend at the knees slightly.

34. Assisted Chest Stretch Variation

Muscle Stretched: Pectorals.

Lie down on the floor, with your face down and palms facing down. Your partner will stand on top of you, and pull your hands back. You should feel a deep stretch in your chest muscles. If your shoulder dislocates easily or if you have had any kind of shoulder injury recently, do not perform this stretch.

This article was originally posted at beyoungbegreen.

Read more at http://livelovefruit.com/34-pictures-help-you-see-which-muscle-youre-stretching/#jUguzq5vbIYIcfg5.99

![Self-regulation “control [of oneself] by oneself"](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55563e14e4b01769086817cb/1542845645966-PO2HGKF5JLUBM45UIWQ3/wee-lee-790761-unsplash.jpg)